04 Feb Wildebeest Migration

WHERE TO SEE WILDBEEST MIGRATION

We are happy to have been featured in an article on wildlife by Horizon Guides. Hans Ngoteya, our Founder shared his thoughts on Where To See The Wildebeest Migration, for an essential guide to planning a migration safari in Tanzania and Kenya. Enjoy the read below.

Sometimes called ‘the greatest show on earth’, the wildebeest migration sees mega herds of almost two million wildebeest, zebras and gazelles continuously travel thousands of kilometres in a broadly clockwise direction from the southern Serengeti, north into Kenya’s Maasai Mara, and back again.

Along the way the herds experience the full circle of life, from mating, to calving, to death – often in the jaws of their many predators: the crocodiles and big cats who are themselves sustained by Mother Nature’s beautiful, if brutal, cycle.

This endless journey sees herds splitting and reforming, retracing their steps before heading onwards again and other variations that can make the whole thing more chaotic than it might at first seem. And though the herds generally follow the rains, it’s not an exact science as to when they’ll arrive at each point – the timing and routes differ from year to year.

Staying at a mobile camp ensures a good chance of seeing the herds, as these properties are moved each season to follow the migration route. If you have the time, aim to stay at two or three camps in different locations in the Serengeti or the Mara, depending on when you travel.

The dramatic river crossings are the most coveted sights – but it’s risky to plan your whole trip around this as the crossings are so unpredictable and it’s far from guaranteed that you’ll be in the right place at the right time. Consider seeing a river crossing a bonus, rather than the sole reason to travel.

The famed river crossings, a classic scene of the wildebeest migration

Ngorongoro Conservation Area & Ndutu Plains

The remote area to the south of Serengeti National Park (called Kusini, or ‘south’ in Swahili) borders the Ndutu Plains in the Ngorongoro Conservation Area, and the Maswa Game Reserve to the southwest, creating a vast region of open savanna interrupted by patches of acacia woodland.

The wildebeest migration passes through the Ngorongoro and Ndutu region between the months of January to March. This is calving season, where the herds of wildebeest (along with zebras and gazelles) swell with hundreds of thousands of newborn calves.

But the open grassland plains and sparse tree cover create an ideal hunting habitat for the big cats and hyenas that prey on the young calves at their most vulnerable. This is a dramatic—and traumatic—time, as the miracle of new life and growth is tempered by the harsh reality of the prey-predator relationship. Lions, leopards, cheetahs and hyenas are all active here.

Bordering the southern Serengeti is the Maswa Game Reserve, with two private reserves, Maswa Mbono to the north and Maswa Kimali to the south. The reserve plays a key role in protecting the Serengeti ecosystem. Successful anti-poaching efforts have boosted wildlife numbers and it provides an essential buffer between the community and the Serengeti National Park itself, reducing encroachments and making it harder for poachers to reach the Serengeti.

Also in the area is Lake Ndutu, a soda lake (strongly alkaline and saline) which is a renowned feeding ground for the lesser flamingo.

Aside from wildlife viewing, the region has some exquisite landscapes with evidence of early human settlement such as rock paintings on the kopjes (rocky outcrops) and Olduvai Gorge, an important archaeological site where, in 1973, some of the earliest hominid remains were discovered.

The Grumeti Rivers, the first major river crossing on the journey north

Central Serengeti & the western corridor

The ‘long rains’ begin in April and the wildebeest sweep up through the southern Serengeti where the mega herds disperse and fan out towards the central Serengeti and, eventually, into the ‘western corridor’.

At the heart of the national park lies the Seronera River and surrounding valley. The Seronera is a perennial river which provides a good habitat for wildlife year-round with resident lions, leopards and cheetahs. Due to its variety of habitats and the permanent availability of water, an abundance of herbivores, such as zebras, Bohor reedbuck and Grant’s gazelles are found in this area throughout the year. Flamingos can also be found at the nearby Lake Magadi.

The landscape here is dotted with large kopjes, a result of volcanic activity in the area, which are a favourite perch for big cats. Simba Kopjes, meaning ‘Lion Rocks’, was the inspiration for the towering rocks featured in the Disney film The Lion King. Among these boulders are the famous ‘gong rocks’ at Moru Kopjes, thought to have been used for communication over the vast plains. Also nearby are caves used by the Maasai until just 50 years ago, complete with rock art.

It’s also possible to spot the last remaining black rhinos in the Serengeti at the Moru Kopjes, south of the Seronera River.

Front runners will reach the western corridor, eventually meeting the Grumeti River – the first major river crossing for the wildebeest on their long journey north. Although the Grumeti is not as wide or dangerous as the Mara, you may see some impressive crossings her

Zebras making their way across the Mara River

Northern Serengeti & the Mara River

Still dispersed, the herds continue north through the Ikorongo Game Reserve en route to the Kogatende and Lamai areas, on the banks of the Mara River.

The Kogatende area in the northern Serengeti is a great place to catch the migration, between July and October but with July and August typically the peak months. There is a permanent pride of lions in the area that you can see year round, along with other leopards and cheetahs.

At the far northern edge of the Serengeti National Park is the Mara River, which provides the backdrop for the famed migration river crossings. The Kogatende is a fine region to base yourself during peak summer months. River crossings occur on a daily basis, and you’ll be sharing the view with far fewer tourists than in the Maasai Mara just across the border.

A family of elephants makes its way across Kenya’s Maasai Mara

Kenya’s Maasai Mara

Kenya’s Maasai Mara National Reserve (Mara for short) forms the northern fringe of the greater Serengeti ecosystem, most of which is in Tanzania.

The herds typically pass through the Mara between June and October. The Mara River runs through the centre of the reserve, and this is prime river crossing territory. During the high summer months the herd will be criss-crossing the river in a chaotic mass of activity, desperately avoiding the crocodiles lurking beneath the waterline.

The Mara is tiny in comparison to the Serengeti National Park, and Kenya is by far the more popular safari destination, so it can feel busy during peak migration months.

There are over 300 camps and lodges in the Mara, ranging from shabby but cheap to something fit for royalty. Prices range from $150 to $1,000 per person per night. You can stay in the reserve itself but the best areas to stay are in the conservancies that fringe the reserve proper. With such a vast range in price (and quality) it’s probably wise to book via a reputable safari specialist to avoid disappointment.

Eastern Serengeti

The Serengeti’s eastern side is a landscape of savanna, punctuated by acacia trees and rocky outcrops – the most famous of which is Gol Kopjes. This is a great place to watch big cats chasing down their prey, such as Grant’s or Thomson’s gazelles.

Around October and November the herd disperses again for its long, and fast-moving, journey south, passing through Loliondo and Lobo areas. Catching the migration isn’t easy at this time of year, but there’s plenty of other wildlife to see and low season means great value for money in some pretty spectacular lodges and camps.

An active volcano, Ol Doinyo Gol (‘Mountain of God’ in the Maasai language Maa), lies beyond the park’s eastern boundary. At 2,900 metres above sea level it’s relatively small compared to the famous Kilimanjaro (5,500m), but it’s still a challenging full-day’s climb. The volcano’s lava flows have enriched the surrounding grasslands, making it an attractive spot for the wildebeest as they return south.

Even further east is Lake Natron, another soda lake which provides a superb breeding ground for thousands of lesser flamingos.

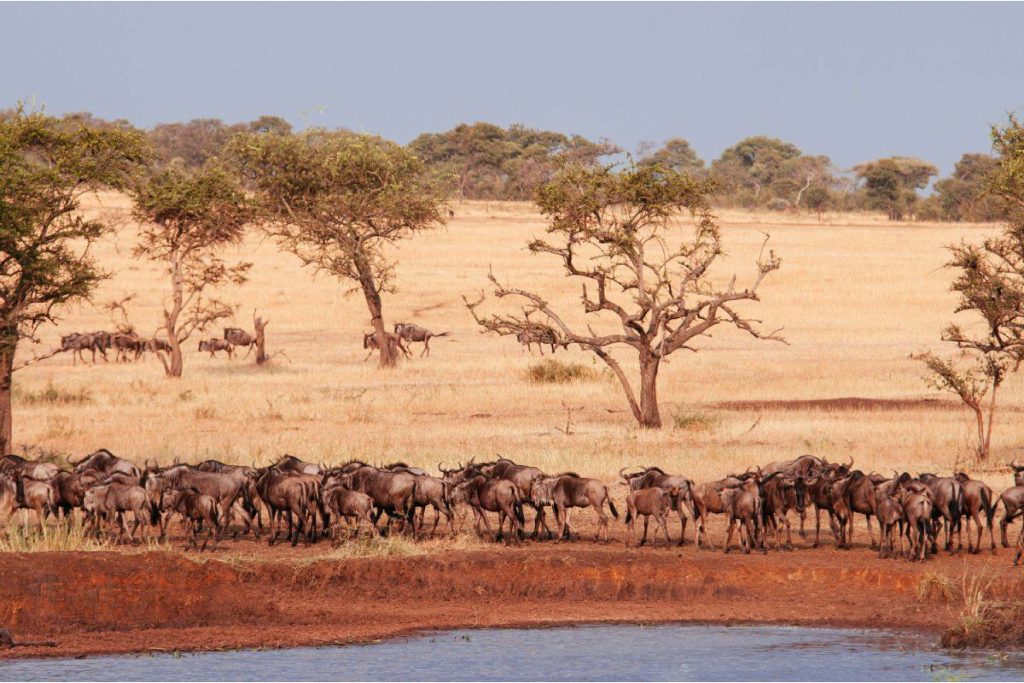

The herd grazing on the Serengeti plains

How to see the wildebeest migration

Migration safaris – Kenya vs Tanzania

Kenya’s Maasai Mara National Reserve is a more wallet-friendly location to see the wildebeest migration. Despite having a shorter migration season, Kenya has more flights, more tourists, stiffer competition, and a greater variety of affordable accommodations than Tanzania.

Tanzania’s size means that travelling beyond the Northern Circuit normally requires internal flights, so getting to the parks in the south and west is more expensive but generally much more exclusive.

Tanzania’s Serengeti National Park is far bigger than the Maasai Mara, with more exclusive lodges and camps in less crowded areas. That being said, the central regions of the Serengeti can still get very busy, so selecting your camps carefully is key.

Generally, Kenya is the better option for family safaris, those on a budget and those with less time to spend. If you want to splurge, get away from the crowds and visit multiple locations, Tanzania could be your best bet.

Where do the wildebeest migrate from and to?

The rhythmic migration has no real beginning or end, it’s more a perpetual cycle that repeats, with variations, year after year. Perhaps it’s better to think of the journey beginning with each calf’s birth in the Ndutu plains beyond the southern Serengeti. From there the herd moves north through the Serengeti before reaching the Mara River and eventually crossing into Kenya’s Maasai Mara, before heading back to the southern plains.

Why do the wildebeest migrate?

Wildebeest migrate around the Serengeti-Mara region following the fresh grasses that sprout after the rains. We don’t know for sure exactly how they know where it’s raining – theories include the smell of the rains, a change in air pressure, and evolutionary instinct.

It’s not just the wildebeest that migrate. Among the herd are thousands of zebras, gazelles and impalas. These mega herds bring advantages beyond merely safety in numbers. Zebras feed on the long, coarser grass, preparing it for the wider muzzles of the wildebeest, who prefer shorter grass. Predators like lions and leopards do not migrate with the herds – their interactions occur when their paths cross.

When the herds start moving, a ‘wavy front’ has been observed, suggesting a level of coordination among the wildebeest. How they communicate this is unknown.

The major predators that prey on wildebeest include lions, hyenas, cheetahs, leopards and crocodiles. However, a fully-grown wildebeest is no easy meal and adults can seriously injure most predators, including lions, using their great strength and horns to impale or toss attackers.

With a top speed of 80km per hour, a wildebeest is also not the easiest creature to catch. When faced with a predator, they will mass together, with younger animals screened by adults. They also employ lookouts as they move, who will call out to alert the herd if they spot a predator. Once alerted, the herd runs in the same direction to deter the attack.

River crossings are one of the most dramatic moments in the migration. While it might seem that the wildebeest choose an arbitrary moment to jump into the water, causing a frenzy of activity, research shows it might be more planned than first thought. A herd of wildebeest appears to have ‘swarm intelligence’ as they systematically explore and overcome obstacles together.

Is the wildebeest migration in danger?

When it comes to conservation, the wildebeest migration is a complex interplay between humans and wildlife. The survival of the entire ecosystem hangs delicately in the balance.

Local communities, development, and tourism

Historically, the Maasai were semi-nomadic herders who could coexist with wildlife. But tourism has encouraged greater settling around parks such as the Serengeti.

The creation of private wildlife conservancies around national parks have been a modest success, allowing local people to earn a stable income from their land, while creating well-managed grazing areas. But booming tourism and population growth have contributed to further expansion, putting pressure on park borders and leading to human-wildlife conflicts.

A changing climate

Another big threat to the area has been the more intense variations in seasonal flooding and drought, which might be the result of climate change. As the Indian Ocean warms and prevailing winds transport moisture over East Africa, more intense periods of rain and drought result, raising the prospect of a new threat to the Serengeti’s keystone species and its migration.

To read more visit Horizon Guides

No Comments